Trappist monks honor enslaved buried in unmarked graves with garden and Christ sculpture

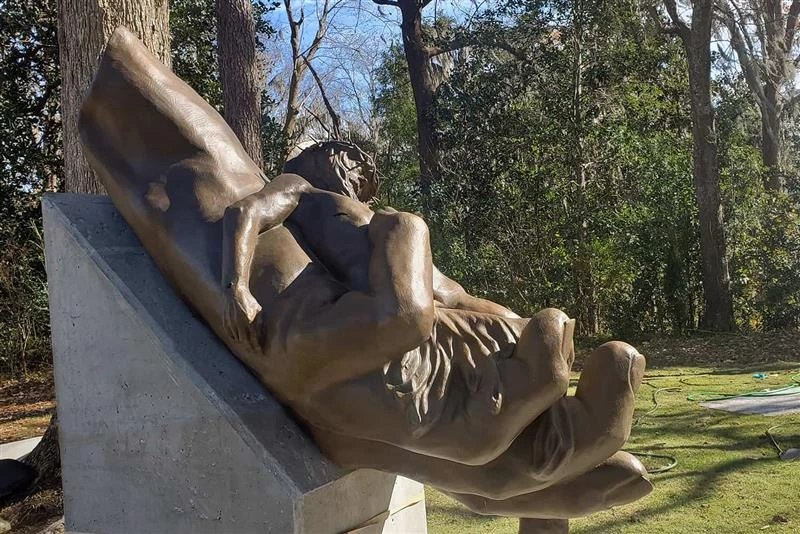

The garden created at Mepkin Abbey is a way to honor and recognize the enslaved who lived and died on the property for 100 years. / Credit: Photo courtesy of Mepkin Abbey

The garden created at Mepkin Abbey is a way to honor and recognize the enslaved who lived and died on the property for 100 years. / Credit: Photo courtesy of Mepkin Abbey Washington, D.C. Newsroom, May 31, 2025 / 07:00 am (CNA).

On a piece of land in South Carolina where hundreds of Indigenous and African Americans were once enslaved, some Trappist monks, after discovering 20 unmarked graves, have installed a bronze sculpture of Christ and created a quiet prayer garden to encourage healing and reflection.

“We’ve been here 75 years, since 1949,” Father Joseph Tedesco, the superior of Mepkin Abbey, a Trappist monastery in Berkeley County, told CNA. “The monks who were here at the beginning — everyone has been aware all these years that this was an enslaved property.”

The abbey sits on a former plantation that once belonged to slave trader Henry Laurens during the Revolutionary War and later to his son John Laurens, who joined the revolution and advocated for the freedom of the enslaved.

There were “300 enslaved people on the property,” Tedesco said. There were “on and off discussions around the memorial to slavery of [the] very historic piece of property; then a few years ago we were just at a moment of recognition … we had to do something, but we couldn’t figure out what.”

As if on cue, Mepkin Abbey then received a 640-pound bronze sculpture from a donor. The large work of art inspired the plan for the Meditation Garden of Truth and Reconciliation — an area on the property that would be dedicated to the slaves who once lived and worked on the property.

“As soon as I saw [the statue],” Tedesco said, “I realized that was the nucleus of the memorial to slavery.”

The sculpture, titled “Thy Father’s Hand,” features the crucified Christ in the hand of God. The figure is now the central point of the garden and is placed where some of those once enslaved on the property lie in 20 unmarked graves.

“I developed a committee of African Americans from around the state and together we created the garden,” Tedesco said. “We walked through together … what to do and how to do it. We created the garden, but it took us a couple of years to put it in place.”

The monk added: “It was really a wonderful experience because it was a lot of editing, a lot of wonderful discussion, and a wonderful group of people who were really committed to the process and to the commitment of building this garden in honor of slavery, but really in honor of being enslaved,” Tedesco said.

When the garden was complete, the first Catholic Black bishop in South Carolina, Jacques Fabre-Jeune, blessed it and discussed reconciliation at an opening ceremony on April 26. He also blessed each of the unmarked graves.

“We don’t have to be upset. Truth can always hurt,” Fabre-Jeune said during the blessing. “We don’t like when people tell us the truth. We feel uncomfortable. But after that experience, we know that it was good for us.”

The new garden is a way to honor and recognize the enslaved, but Tedesco said the monastery is really the memorial to them because of the “75 years of praying on [the] land to redeem it from the 100 years of the enslaved on [the] property.”

The garden is now open to visitors who can walk through its multiple stations that each reflect points of history. The monks hope the experience will encourage “empathy” and “understanding.”